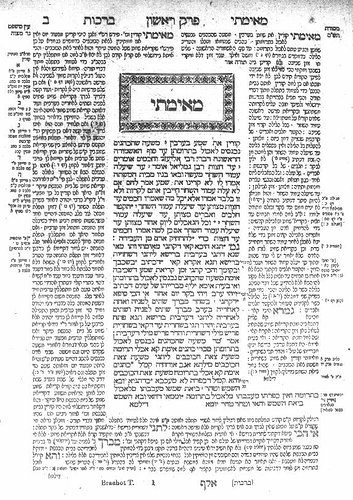

The Talmud is often printed in such a way that multiple commentaries on a text appear around that text, but in a way that visually distinguishes them as less authoritative than the central text, viz:

My interest is not biblical, but I wanted to offer this as a visual. What I am interested in is creating a Tinderbox document composed of multiple layers, where each layer has a different degree of authority. (Layer is not meant in a literal sense, but I haven’t found a better descriptor.) The base layer of the document would be the most authoritative information, with additional layers stacked on top adding additional information that is less authoritative than the layer it rests atop. In the simplest non-trivial case of two layers, the base layer would constitute an authoritative version of the document, and the other layer would provide additional information to the base layer, without permanently obscuring it. The physical metaphor here is a stack of transparencies, where the transparencies on top can be removed to look at and make changes to the transparencies lower in the stack.

The central use that I’m driving at both with the Talmud visual and layer metaphor is that I would like to have a Tinderbox document that includes a great deal of information taken from authoritative sources and organized to my taste. I then want to add my own thoughts and amendments without losing the ability to add to and refer to the underlying document composed of authoritative text without the changes I’ve authored.

I have only scratched the surface of what Tinderbox can do, so I thought I would ask the forums: is any of this something that Tinderbox supports? Or am I better off writing tools to manipulate the underlying XML in the ways that I’m trying to accomplish?

Thanks for your advice.

(Image from File:First page of the first tractate of the Talmud (Daf Beis of Maseches Brachos).jpg - Wikimedia Commons)