Precisely. I have huge admiration for Tinderbox as a tool (I’ve probably spent far more money on it over the last 15 years than any other software I’ve ever owned  ) but for the specific task in the OP, Scrivener is a much better fit than Tinderbox, as it has built-in features for dealing with and revising an existing Word document in exactly the three stages @mwra suggests: Ingest, work/review, output.

) but for the specific task in the OP, Scrivener is a much better fit than Tinderbox, as it has built-in features for dealing with and revising an existing Word document in exactly the three stages @mwra suggests: Ingest, work/review, output.

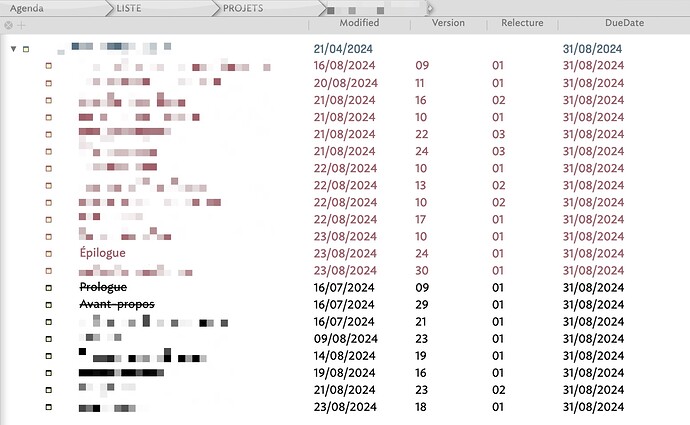

@wajakob: It’s too complicated a topic to detail in a post, but essentially you can import the original word document into the Scrivener project and have it automatically split it into its constituent chapters, sections, subsections etc, each of which can have its own metadata (status, keywords, custom fields), and each of which can either be viewed singly, or combined into an editable ‘virtual’ document on the fly (for example, to see all the sections dealing with a specific topic in one go, even if they’re not consecutive in the outline).

Your footnotes will be imported correctly and be converted to the Scrivener equivalent.

You can take snapshots of each document in the outline separately to compare and roll-back changes you make, and you can have both the original and your new version side-by-side in the editor (and can have an arbitrary number of other documents open at the same time for reference).

Each document can have individual reference links to other internal or external documents, as well as links that are globally relevant: when you click on these links their contents are immediately visible without leaving your text. Incorporating any new research document into the project is trivial. You have a direct link between your document and your Reference Manager – basically, you press cmd-y in your text, which opens, say, Bookends. You select the reference in Bookends, press cmd-y again and the citation is inserted into your text, in the format you choose.

Depending on how complex your final document is, compiling it back to Word can be as simple as pressing a button and choosing a default compilation format, but it’s also flexible enough to incorporate complex needs, such as integration with Latex, and that is inevitably more complicated to achieve. But many academics use Scrivener for exactly this sort of process and will be happy to give advice on the relevant forum.

Doing much of this may be possible in Tinderbox, but for much of it you’d be devising your own solutions to fit your specific needs – that is after all what Tinderbox is, a toolbox in which you’ll build your solution.

It’s feasible, but it will be an awful lot simpler in a tool which is designed to do this specific job. That doesn’t mean that Tinderbox wouldn’t be very useful in thinking about the task and taking notes on it, as @eastgate suggests, but the eventual revision and compilation will be much simpler in Scrivener.

If you’ve not already got a version of Scrivener, then they have a 30 day, no restrictions trial.