Fascinating discussion, and the feedback is very appreciated.

There is, perhaps, a broader, underlying issue that is exposed by this debate, and perhaps one that deserves greater examination/discussion in the “General Guidance” container.

Early last week a somewhat familiar question was posed. I tried to offer what I felt was a helpful reply to a difficult question, and I think it is indicative of the broader issue.

We have had many discussions about the expectations that new users’ previous experience impose on Tinderbox. “It’s an outliner!” (Mind-mapper, chart generator, timeline plotter, database, etc.) These, in nearly every case, are impediments to early understanding and productive use of Tinderbox, as expectations inevitably bump into confounding behaviors that can lead to frustration or misunderstanding.

I’m more comfortable with Eastern philosophy, though I’m not unfamiliar with Wittgenstein, but I think you, @andreus, make the case that a philosophical approach is valuable when encountering Tinderbox for the first time. Or, perhaps more importantly, after some early positive experiences with the app, where one’s prejudices and misconceptions may have already been validated.

Perhaps I should have kind of modeled my approach on Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, rather than The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. I chose the latter because I wanted the document to be approachable, light-hearted, but still worthwhile. But it seems like Tinderbox does demand a more philosophical approach, at least at first, to wit: Beginner’s mind.

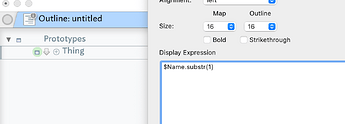

This relates to the question of $Name as its seemingly mundane nature may conceal a value and importance in the user’s relationship with the document and how that facilitates the goals or objectives of the document itself.

To me, it has often felt as though $Text was the premiere attribute and I often regarded $Name as kind of a necessary distraction, something I had to dispense with quickly so I could get to the important attribute, $Text.

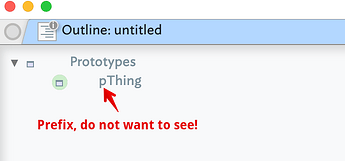

Truthfully, I still do not understand the objections of the people view a prefix notation as somehow polluting something. I’m not saying they’re wrong, I’m saying there’s a gap in my understanding, because they seem to appreciate some additional value in a “pure” (unpolluted?) $Name.

But it is evidence of the importance of $Name, and, to my knowledge, that has not been a topic of much discussion, apart from this sort of, to me, stylistic debate. And it makes me wonder if the value or importance of $Name deserves a greater examination in a document that is intended to illuminate some of the more distant corners of Tinderbox?

Not that I want to get into analysis paralysis, or a “gumption trap,” but it just feels like I ought to be able to articulate the value or importance of $Name more clearly than just the question of whether or not to use prefixes, and whether or not they represent some sort of crutch or artless use of Tinderbox.

How do we write meaningful $Names? What is their value within the document, other than perhaps as a label for the contents of $Text?

Seems pretty fundamental. Am I wrong, or getting off track?