This will be a long answer but stick with it…

(BTW the following is on paper page number 215 of The Tinderbox Way v3, but is on digital page 224 of the PDF.

In the book, @eastgate helpfully splits the code onto lines - to help the reader parse the (sequential) parts:

$Subtitle=$Name(find(descendedFrom(/draft))

.sort($Modified)

.at(-1))

And, in fairness the text that follows on pages 215–16 does break down the meaning if the syntax. But, let’s try again. Note: the syntax colouring is applied by the forum and doesn’t follow Tinderbox’s methods, but that’s a whole different deal. Meanwhile, we can decompose the above code even more, in a different way, to add clarity for discussion:

$Subtitle=$Name

(

find(descendedFrom(/draft))

.sort($Modified)

.at(-1)

)

You ask:

Not same, but a different note. Why? The basic form of setting an attribute value works like this:

$AnAttribute = "some value";

$AnotherAttribute = 4;

$YetAnotherAttribute = date("today");

...etc., depending on the varying types of data being used

But often we want to set a value already stored in an attribute. Thus:

$AnAttribute = $DifferentAttribute;

always sets attribute AnAttribute to the value of attribute DifferentAttribute of the current note unless we tell Tinderbox to look elsewhere, which involves parentheses attached to/following the right-side attribute. Thus by using another note’s title in quotes ($Name):

$AnAttribute = $DifferentAttribute("Some Note");

or its unquoted full path ($Path):

$AnAttribute = $DifferentAttribute(/A container/Some Note);

Both do the same. Indeed you can do the same on the other side or both (unusual but the need could arise:

$AnAttribute(/A container/Some Note) = $DifferentAttribute;

$AnAttribute("Another Note") = $DifferentAttribute"Some Note");

The first, title-based form, is shorter and so generally most people’s preferred usage. So why would you need the path-based form? Well, what if you have two notes both called “Some Note”?Tinderbox happily allows this, as the note’s title is just an attribute (Name) and the the unique identifier is actually the ID (again … an attribute) which is a long numerical number; you don’t need to bother about the latter, it just ensures note A and note B had different IDs. The path-based way of referring to a note allows closer-grained specification of the intended target note. Otherwise, if faced with a choice, Tinderbox will always choose the match with the lowest ‘OutlineOrder’ attribute value.

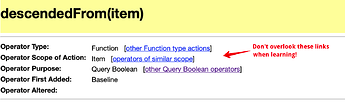

At this point if we don’t know what descendedFrom does, in terms of outcome. So, rather than guess we can look it up. We can use the app Help or look online at aTbRef†. The latter has a set of links top/bottom of every page with links to listings of major code related things like export of action code.

As descendedFrom is action code, the ‘Action Codes’ link looks like a good bet. That shows us an alphabetical list of actions and sure enough descendedFrom(item) is listed. We then find that:

…it matches all descendants of item however deep the outline branch beneath it

So, descendedFrom(/draft) is looking for notes descending from the note draft.

We are sorting the output of the previous operator. Chained dot operators, work in a chain (goring in succession from left to right—thus the term. Resolve the first, apply the next, and so on.

By contrast, if each part of the above sequence of action were a non-chained function we would end end up with nesting looking like this (N.B. the following is not valid Tinderbox code):

at(sort(find(descendedFrom(/draft)),$Modified)-1)

Now where do you start trying to make sense of things. Actually in the middle - in the innermost part, as you would with an Excel expression. But, chained operators are actually easier to read once you get the hang of them. As dot expressions didn’t arrive until Tinderbox v4.6, you may well see two forms of some functions, e.g. format() and .format() and these are generally interchangeable. Indeed, older code samples you may see around likely use the non-dot-form but can easily be translated into the dot-operator form.

Why does this matter? Both are a form of multi-value listing and once wrote the result, as passed elsewhere is the same. The sort doesn’t alter the original, it sorts output based in the original. Otherwise, the .sort() would move notes around the outline that matched the find(). The .sort() doesn’t pick anything from the list, it simply sorts the order of the list that it is passed by the preceding operator

Why use the input $Modified and not "Modified", i.e. an attribute value reference rather than simply the name of the attribute on which we want to sort? Well, we’re telling the app we want to sort a list but using a different list of value, i.e. the list of values of the attribute named"Modified" (ergo, $Modified) but only for the items in the list passed to .sort().

Finally, it is the .at() operator that picks a single item from the list. If we look at the documentation we see .at() uses a number running from 0 (zero) for the first character, up to the length of the list and with the extra affordance of minus numbers (starting a -1) numbering from the end backwards.

So, we are getting the last item in a list sorted on date (which sorts chronologically), and thus the most recently modified item. Those items are all the notes descending (in outline terms) from the note ‘draft’. Furthermore, at this is quotes as starts with a /, we know ‘drafts’ is a container note at the top level of the outline. So we get a single descendant of ‘drafts’ which is that which was the last to be modified and it is that item which is the note whose $Name is passed to set the value of $Subtitle, and so create the current note’s subtitle in map view (only map view displays a subtitle in the view pane).

Is that true though? If I look at the TB-Way’s chapter 12 (paper page 200 onwards), I see lots of use of parentheses, e.g. bottom of paper page 201. So, that critique seems slightly unfair. Still, why parentheses are used at all is a fair question and one I do think merits better answer, though understanding/intuition is very variable amongst readers and its hard to write for everyone’s foibles. Pick any good widely-used teaching book and you’ll find a few students who just don’t get the presented info but happily use a different author’s book on the same subject.

If one is just guessing by putting in things like parentheses when unsure, rather than following documentation, I’d suggest that’s not a good approach. If the documentation says use operatorName(input1, "input2) then do so: provide two inputs in parentheses, the first without quotes and the second with quotes. Or certainly do so at least until you’re comfortable enough to know where you can colour outside the lines. That’s certainly why aTbRef is more precise than the Help because when ‘code’ all seems like a set of magic incantations, simple rules help one safely get going.

Google? Not great as Tinderbox is a smaller user community than, for example, Python users or people writing HTML, etc. You may find something in Google but most likely it will be pointer to Eastgate’s website or aTbRef (I suggest you try both those resources first).

The forum? Yes, it is exactly the sort of thing to bring here, e.g. “how do I find the most recently modified descendant of a particular note?”. I’d like to think this forum is both responsive (in terms of getting an answer quite quickly—even if a direction to another resource) and friendly in tone. We can’t account for people’s experience in other forums: experiences there may vary!

I’d politely counter that does that matter, unless you understand what such a difference implies? It’s not that it is a silly question, but more that it doesn’t help you get to grips with the code. Tinderbox action code does include a lot of features common to general programming/coding. However, the names of operators and syntax for their use vary massively between coding languages so the value of the above question, whilst well intended is—in reality—moot.

But wait, that same article has a link titled “Ways to define item” which I’m guessing you didn’t follow. If you do, it takes you to a note " Notes as ‘item’ objects in action code" which goes through some detail how ‘item’ might be defined as an input.

But, we might ask, “Why not put that in the article on descendedFrom() so I don’t have to waste my time following links and can read it all in one place?” Well, over the 14 years I’ve documented Tinderbox, action code has grown significantly both in scope and complexity and so the meaning of ‘item’ has changed too. There are now 211 operators listed and it makes much more sense to write this ground truth once and link to it rather than update 100s of documents each time (pity the poor author!). Plus, once you’ve learned about item, you don’t have to skip though lots of now known stuff and only keep an eye out for exceptions. Also, the whole concept of hypertext is the user follows links: you go to the content you want rather than software guessing what you want to see.

That sort of suggests this would be clearer:

$Subtitle=$NamefinddescendedFrom/draft.sort$Modified.at-1

I’m less sure.  For all the hoopla about AI, it still sucks at understanding human-written text. Plus, most apps aren’t even using AI. So we need to signal our intention in what may seem a rather pedestrian manner. But think of going to another country that speaks a language you don’t know and using a written script you can’t read. You need a guide book (documentation) and—until—you can speak the language like a native, to stick to standard constructs and simple instructions.

For all the hoopla about AI, it still sucks at understanding human-written text. Plus, most apps aren’t even using AI. So we need to signal our intention in what may seem a rather pedestrian manner. But think of going to another country that speaks a language you don’t know and using a written script you can’t read. You need a guide book (documentation) and—until—you can speak the language like a native, to stick to standard constructs and simple instructions.

Going back to the starting code, we want the title of a note, but not the current note, and which we can only define via a query. We could use an agent, indeed, as described on p215 of The Tinderbox Way. But, to do this in an action we need to use the find operator to handle the querying task, enclosing the the query in parentheses, e.g. find(query), to indicate to the app that the query is an input to the code the app runs in response to a find request.

In summary, I think the info is there (though I grant it can be improved‡). The issue is how one engages with it—and that’s not criticism. As noted above, computers aren’t smart enough to understand us (ever tried asking Siri, Cortana, etc. to do anything non-trivial?). So, we have to signal our intent to them in terms they can understand unambiguously. We humans are, of course never ambiguous in our statements.

I’d try to avoid treating this issue of understanding Tinderbox action code as a binary case of understanding all or nothing. Insight takes a few iterative steps, each new revelation underpinning a wider understanding and eventually the ability to guess where things may may not work.

As an endnote, when looking at the listings of operators and attributes, don’t over look the links in the Displayed Attributes-like tables at the head of the page, e.g.

Lastly, actionable suggestions for additions/improvements to aTbRef are always welcome as is information on typos, errors, out-dated info, etc. There are many notes in the ressource and I’m a really poor typist!

†. Disclaimer. I’m the sole author/originator of aTbRef

‡. Bear in mind that Eastgate doesn’t have a documentation department and aTbRef is written in my spare time (whilst also running this and the Backstage forum). The fact that I’m just a (licence-paying) user—and beta tester—means I’m able to document things Eastgate is still working on right up to release point allowing the resource to include things that may slip from the app Help. TL;DR the resource for documentation is small…and finite!).

[Edits: for typos/better sense]

Also, I’d just fixed that. I find the rendered article much easier to proof that the raw Markdown. <sigh>.

Also, I’d just fixed that. I find the rendered article much easier to proof that the raw Markdown. <sigh>.