One use case for Tinderbox is storing information, then applying techniques to traverse that information to produce certain outcomes, e.g. a book, an article, a web page, a conference, a dashboard, a dynamic list of tasks, etc. Many applications could do this, but Tinderbox offers a flexibility in the structuring of that information that seems to me unmatched. It handles irregular information, as The Tinderbox Way highlights, while offering automations that can impart degrees of regularity.

The use case I have in mind is as a prosthetic for thinking. Here there is no outcome in mind except better thought, because clearer, more refined, more profound and so on. In this case, we use Tinderbox to create relations between elements. Again, The Tinderbox Way highlights this feature of Tinderbox, noting the variety of relations that can be created such as containment relations, hierarchical relations, spatial relations, contrastive relations, a/symmetries, commonalities, derivation (e.g. parent/child). And these relations can themselves be related, thus creating orders of relations.

To make this use case somewhat more concrete, we can imagine that what we are engaged in is conceptual topography. We can create or discern a map of the concepts (or ideas) where a map is simply a set of inter-relations between elements, just as an ordinary map is a set of spatial inter-relations between buildings, streets, hills, streams and so on. We can conceive ourselves as reviewing our information (ideas, concepts) so as to discern their actual inter-relations and then represent these in Tinderbox. Or we can conceive ourselves as creating their inter-relations which we represent in Tinderbox. In fact, this distinction between conceiving and discerning will not last, because even where we imagine that there are actual inter-relations, our representations creates new ones. If I represent a passage through a countryside (map) in one direction, some things (e.g. houses) appear on the left and some on the right. If I represent the route in the other direction, the same things appear, now reversed with respect to left right. This is so for any map and a perspective on it. So how I represent things is very important to how they are presented, to the relations that appear to me, to how I think about them.

Again, to make this more concrete, we can use a historical example. The Austrian philosopher, Wittgenstein, was unable to arrive at suitable presentation of his later philosophy because he felt that what he needed to do was criss-cross the conceptual topography he wanted to present, over and over again, because each route across the conceptual landscape would produce different intellectual illumination. The linearity of a book worked against this. Tinderbox may or may not offer a solution to the problem of presenting or publishing a conceptual topography, but it certainly offers a powerful tool for doing the thinking involved. (Wittgenstein resorted to obscure parallel numbering schemes, or to cutting up copies of his ideas and re-/arranging them with glue–none of which satisfied him.)

The key idea from these examples is that each route through the concepts (ideas) is a distinct set of inter-relations between them, where inter-relations are those that can be represented in various ways using Tinderbox.

This is how I am using Tinderbox to the best effect. However, I have found a shortcoming, and I believe that fixing this shortcoming would permit an additional, powerful way of using Tinderbox.

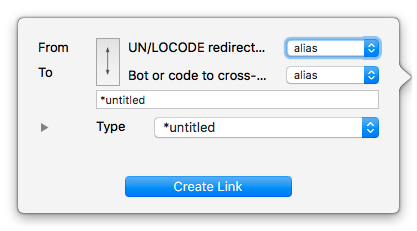

The shortcoming is with aliases. Creating an alias creates a de facto relationship between the original and the alias, which is hierarchical or asymmetric because the two are not duplicates in the right sense. But really I do not want to create that relationship, I would like something that is self-identical in almost all ways. I do not want to have to make decisions based on whether I am using the alias or the original, because the relationship is not meaningful in relation to the content of the notes, that is the idea (concept) with which I’m working.

Again, let me give a specific example. I may have a note whose content ($Text) is the idea that evil is the privation of good. This note has my current thinking on that idea, which, as clarity comes to me, I will augment with further thoughts about that idea. Now I want to use that idea in several places in my conceptual topography. I would like to relate it to the metaphysics of good and evil; to the asymmetry of doing good and avoiding evil; and to the content of moral thought. The relations may not all be the same, however. In one I may want to place it in a container. In another I may want to put it in a web of links. In the third I may want to position it spatially near and above some other ideas. No one of these inter-relations is primary, so none is the natural place for the original, or indeed the alias. Why should I have to make this choice? Why should I have to remember this choice? Why will any automations (e.g. rules) have to take account of whether this is the original or the alias? There are consequences too, if I delete the original, my aliases disappear too; though not the reverse. Parent child relations are degenerate between originals and aliases, for example.

The solution, it seems to me, is to have duplicates of notes that are self-identical (in the relevant sense) so that there is no implicit hierarchy between them. In DevonThink this would be called a replicant. In some UNIX-based filesystems this is what you get with a so-called hard link. In my case, I’d like one idea to occupy two (or more) places in my structures of thought as represented in Tinderbox. In the file system case, there is one content (the file) but more than one “address” or entrypoint to the content, viz. places in the filesystem directory structure. The directory structure is really just a space of names and there is no problem if two names (e.g. /a/b/c.txt and /a/e/f.txt) refer to the same thing, just like there is no problem if Clark Kent and Superman refer to the same extra-terrestrial. Obviously there is a difference if he is introduced to you as Clark Kent or Superman, but that is the point: each name provides a different re-/presentation of that person. That is what I would like to capture in my thinking as represented in Tinderbox.

There could still be an indication in Tinderbox that a replicant had a counterpart (i.e. the replicant with which it was self-identical just as the italics indicate aliases). In DevonThink the names of records are shown in a different color, but you could also have a flag or replicant count appended to the note name.

The point of a replicant, like an alias, and unlike a duplicate, is that when you add to or amend the content (i.e. $Text) you are changing it for all replicants. So if someone asks whether I cannot achieve my multiple routes through the same conceptual topography in Tinderbox by simply putting one set of relations into a container, duplicating the container, and then changing the relations in the new container, I reply that I cannot because then when I edit the note in one container I have to edit in all the other duplicate containers.

–> Have I missed something? Is there some way to achieve the functionality of replicants as I described them in Tinderbox today? Is there a good way to meet the use case I’ve set out without replicants? (I should say in advance that I do not think tagging will work here or, if it does, the overheads thus created are not worth it.) I say this also having reviewed the discussion around John Weiland’s mention of replicants in January on this forum, in which I never quite understood the use case. That is why I’ve tried to set out my use case (or cases) more clearly. I also noted Mark Anderson saying Tinderbox does not currently do this: I get that, which is partially why this is in Off the Wall and also is a kind of feature request.

While thinking about this problem and the obstacles to implementing it in Tinderbox, I realize that there was a kind of mismatch in my thinking that might (or might not) be reflected in Tinderbox, which is what leads to aliases. Aliases are tricky to implement because, as the design note on them in The Tinderbox Way notes, it is unclear which attributes should be essential to the alias and which should be shadows (i.e. duplicates) of the original. However, if you think the content (of the idea) that the note contains is fundamental, this problem goes away. All that matters is whether the content of the note is identical. If it is, then two notes are replicants. You can conceive the content as $Text or $Text+$Name without consequence, though you do have to choose either one or the conjoined pair. These are the essential attributes that determine the identity of notes, all the other attributes are inessential or accidental. Tinderbox, I believe, treats the note, rather than the content, as fundamental, which is why so many more attributes have to be considered essential. If that is right, then it seems to me that one way around this is to think of a note as a container for a content. Content is identical irrespective of the notes in which it appears. Notes could be made more or less identical according to various sets of attributes taken as essential, so there could be a variety of alias types or the current one.

I’m not arguing for getting rid of aliases. I see their value in agents, where the agent effectively synthesizes references to notes, rather than notes. No doubt there are similar places where an automated operation is best done with aliases.

If replicants existed for content, then I think we could be looser with notes. A future Tinderbox could offer what I will call “possibilities” which is at root, the same content with different structures of notes. Another way to put this is that a Tinderbox document would contain content (as I’ve described it above) but many possibilities for how that content is distributed into notes. Again, to give an analogy, over time, the world contains the same individual people, at different points in their lives. Those lives have different possibilities, but for most of those possibilities, whichever become actual, the people remain, i.e. they are the same person–Tom may get that job or not, but he is still Tom whether he does or not.

The idea is that in Tinderbox (version 8?) a document would have different organisational structures–i.e. the same content in two maps or two outlines, all four different, differing perhaps even in the numbers of notes in each–where each collection of relations is called a possibility. The number of contents would be constant across all possibilities. At the UI level, you could tie each possibility to the same window, i.e. each window contains solely views on one possibility. Leaving aside implementation complexity, why not? I think we’re talking about different logical spaces for the same entities.

One “cheap” way to implement this would be to permit the creation of inter-document replicants. Then each document would be a possibility, though you would still have to make sure that the totality of entities (i.e. all the entities), where, on this approach an entity is a content, was the same between documents. This means synchronizing entity creation and deletion, which might be ugly in terms of user consent and notification.

At any rate, the implementation difficulty is not something on which I can speculate, nor whether this feature would be of value to more than a few users.

–> I would be interested in other people’s thoughts.

I apologize in advance if there is something rather naïve about my discussion and proposals. I have been using Tinderbox for only about a year, and I do not have much grounding in the hypertext movement out of which it originated. I believe that might urge a presumption of directionality to the thinking behind Tinderbox. So it could be that this is an amateurish re-hash of some well-trod ideas. If so, I’ll welcome directions to concise presentations of these ideas. Mainly though, I’d like to make better use of Tinderbox for my own thinking, so I welcome suggestions of any kind in that regard.

David.